|

I'm really pumped about the director and cast for "Election Day," my play which debuts at Borderlight Theatre Festival on July 25, 26 and 27 and aims to explores our common humanity through the voices of Ohioans on the way to the voting booth. (More info and buy tickets here: https://www.borderlightcle.org/election-day/).

So, I wanted to take a minute to introduce them! Some of these folks are veterans of the stage, while others are excited to be acting after a hiatus, but they're all super talented. I'll send out updates as folks are added. Read below to check out who's who! Jimmie Woody, director Jimmie Woody is a director, actor and writer whose recent directorial credits include Jitney by August Wilson at Beck Center, Brownsville Song/B-Side for Tray at Dobama Theatre, Art of Longing by Lisa Langford at Cleveland Public Theatre, and others. Jimmie received his M.F.A. in acting from Columbia University. He was a 2019-2020 Cleveland Public Theater “Premiere Fellow'' and a 2012 Creative Workforce Fellow in theater. He is the Director of Community Programs at the Center for Arts-Inspired Learning and a former film instructor at Cleveland High School for Digital Arts and acting instructor at Cuyahoga Community College(Tri-C). Junyoir Fraley Junyoir Fraley is a young lady on the rise. She is so excited to be making her stage debut here at the Border Light Festival. Junyoir has been seen most recently in a Mother's Day Nike Promo for Kicks Lounge and was featured in The Cleveland International Film Festival's 47th Trailer. She enjoys swimming, laughing, and creating content. She is looking forward to the journey ahead of her. Cheryl Games Cheryl Games Cheryl is a playwright, actress and arts marketing professional. She is thrilled to be making her Cleveland debut with the fabulous cast, director, and playwright of Election Day. Previous acting roles include King Lear (Kent) Bloody, Bloody, Andrew Jackson (Storyteller), A View From the Bridge (Beatrice), Picnic (Flo), Macbeth (Lady Macbeth), Dinner With Friends (Karen), Blithe Spirit (Elvira), and Circle Mirror Transformation (Marty). Her plays have been produced in New York; Los Angeles; Greenville, SC; Pittsburgh, PA,;and Columbus, OH. Education: M.F.A., Actors Studio Drama Program, New School University; M.B.A., The Ohio State University. Cheryl and her husband, David, live in Cleveland with their roommates, Astro and Cocoa. #goguards Joseph Milan Joseph Milan is thrilled to perform in his first Borderlight Theatre Festival! He extends his heartfelt appreciation to Lee Chilcote, Jimmie Woody and his fellow cast for such an important and timely piece. Joe's recent stage appearances were in “Mother Courage and her Children” at Ensemble Theatre and ”A Fugitive’s Lesson” and "Wenceslas Square '' at Ceasar’s Forum. Please check your voter registration and prepare for “Election Day IRL” this November! Angela Moore Angela Moore is a single mom to three amazing kiddos and lives in North Ridgeville. With a bachelors in theater from Miami University, Angela is ending a 20 year hiatus from the stage with a role in Election Day. Angela has performed in shows like A Christmas Carol, Bye Bye Birdie, Into the Woods, Clue, Last Call and a number of independent plays and films over the years. In addition to acting, she has worked tech on shows including South Pacific and True West. She has also written and directed a handful of plays as well. When she is not performing or spending time with family, she is selling real estate, visiting historic sites, teaching, reading, writing or knitting. Angela is passionate about the arts and is on the board of Literary Cleveland, helping the organization in its mission to support and encourage writers in Northeast Ohio. Sophie O'Leary Sophie O’Leary is a sophomore at The Ohio State University double majoring in theatre and music. She is so excited to be part of the Borderlight Theatre Festival for the first time and this wonderful show! Since 2015, she has performed in over 20 shows in the greater Cleveland area. Past credits include The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee (Olive) at OSU, All Shook Up (Natalie) at Near West Theatre, and Cinderella (Cinderella), Clue (Mrs. White), and 9 to 5 (Judy) at Saint Joseph Academy. So many thanks to her amazing family, the hardworking team that made this production possible, and YOU for supporting live theatre! Enjoy the show! Perry Reed, actor Perry Reed has been acting for four years and received theatre training through the Karamu House and film training with Angela Boehm. Credits include Stonewallin’ at Convergence Continuum, Temptation of Adam at Cleveland Public Theatre, Rivers in Ink at Karamu House, The 2023 & 2024 Marilyn Bianchi Kids’ Playwriting Festival at Dobama Theatre, and Comma at Blank Canvas Theatre. He has also done various film and commercial work with Cinema Central, Covered in Content, T.H.A League Productions, and more. He co-wrote and starred in Mirrior Mime and The Loop with Arev Studios. Tamicka Scruggs Tamicka Scruggs received her bachelor's degree in Television/Film at Clark Atlanta University. She is currently the assistant property manager at Mt. Hermon Good Samaritan. Tamicka has been seen most recently in the AMC series “The Walking Dead,” “The Gateway,” the Lifetime movie “With this Ring,” and on Showtime in the documentary “Murder in the Park.” She has performed in many theaters around Northeast Ohio including Dobama Theatre, Near West Theatre, Weathervane Playhouse, Karamu Theatre, Blank Canvas Theatre, and The Fine Arts Association and has been involved in many reenactments with the television show “Crime Stoppers.” In addition to being passionate about theater and acting, she also loves to coach basketball and write music.

0 Comments

In the runup to the last presidential election in 2020, I had voices in my head. No, not those kinds of voices. These were the voices of characters speaking their truths. Some were based on my own experiences, some were based on stories I'd heard, and some were entirely fiction.

These voices, while all different, had one thing in common. They were grappling with how the headlines we read every day were affecting them personally. Issues like gun violence. Police brutality. Gerrymandered elections. Hyper partisanship. The rise in hate. I took these voices and their struggles and turned them into a short play called "Election Day" that will be staged as part of the Borderlight Theatre Festival at Playhouse Square next month. The premise of the play is simple - Ohioans from different political backgrounds and walks of life tell their stories on the way to the voting booth. The play poses the question, "Are we really so different?" and strives to explore our common humanity amidst political differences. "Election Day" will run at the Hermit Club at Playhouse Square as part of the Borderlight Theatre Festival on July 25, 26, and 27. It will be directed by the amazing, talented Jimmie Woody. I hope you'll come out and support it. Details and tickets are here: Election Day - BorderLight Festival (borderlightcle.org). (You will also want to check out Borderlight generally, and all its great shows -- we went last year and had a great experience.) In the meantime, here are a few ways you can support the play:

Audition Notice! My play "Election Day" was accepted into Borderlight Theatre Festival this August, to be directed by Jimmie Woody, and we're holding auditions on June 19 and 20!

http://www.borderlightcle.org/election-day Looking for a few good men and women to play multiple characters in multiple scenes. Synopsis: Exploring our common humanity through the voices of Ohioans on their way to the voting booth. Auditions will be held June 19 and 20th from 6 PM to 8 PM at the Brownhoist at 4403 St. Clair Ave. (see flyer). Please have a monologue prepared or read from sides given at the audition. Borderlight Show Schedule: TECH: July 24th | 11AM SHOW: July 25th | 7:30PM SHOW: July 26th | 7PM SHOW: July 27th | 6:30PM Venue: Hermit Club; 1629 Dodge Ct, Cleveland, OH 44114 Stage: Great Hall QUESTIONS? Send me a message, happy to chat! (Note: This is part 3 of a series on the life and death of St. Agnes Parish in Cleveland's Fairfax neighborhood. You can read the other parts at www.leechilcotewrites.com.)

As white families moved out in the 1940s and 1950s and the Fairfax neighborhood became more diverse, a forward-thinking priest at St. Agnes Parish named Bishop Floyd L. Begin tried to create an interracial church community. Bishop Begin, who was priest at St. Agnes from 1949-1961 before he was called to head up the Diocese of Oakland, worked to stem the tide of middle-class flight from the neighborhood by telling his parishioners that they “can live in a better neighborhood without moving.” He also called on them to stay for moral reasons – according to a Dec. 31, 1951 article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, he touted the “theory that improving neighborhoods leads eventually to improving cities, states, nations – and human beings.” In 1960, seeing church attendance decline as white families moved out to the suburbs and created their own churches, Begin held talks on Catholicism at St. Agnes as a way of attracting new parishioners from the increasingly Black neighborhood. “We want to make non Catholics feel at home,” he told the Plain Dealer on Sept. 10, 1960. Begin used posters, billboards, and radio and newspaper ads to get the word out, and also sent letters to all the ministers in the area. The Plain Dealer covered Begin’s outreach as a notable response to the “changing character” of the neighborhood – the newspaper rarely mentioned segregation, racism and poor housing conditions in its coverage. Begin, on the other hand, was not shy about talking about race, segregation, and racial justice issues. As the Civil Rights movement was brewing in Cleveland and across the country, he promoted St. Agnes as an integrated parish. His language is dated now, but it was progressive then. “The Catholic must look at the Negro in the light of the doctrine of incarnation and the doctrine of redemption,” the PD reported him saying to his congregation in an Oct. 22, 1960 article. “We are all blood brothers. Children of the same father. God created the whole human race. He must have liked the dark skinned people, because he created them.” He added, “Jesus Christ became man to make man a God and the only way he could do it was to become one of us. To exclude any one of the human race from an opportunity to gain eternal salvation is to exclude Christ.” In 1954, Bishop Begin stirred up controversy with his support of an interracial group that was seeking a Knights of Columbus charter. His efforts were unsuccessful – the Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus in New Haven, Connecticut turned down the Cleveland and Ohio group’s request that a charter be issued to an interracial group. Nonetheless, Begin drew national attention for taking a stand in support of integration. After being turned down, he declared, “The only reason they're being kept out is their color. Anyone who denies that is a pussy-footing liar,” according to his April 24, 2977 obituary in the New York Times. Instead of shying away from the issue, Begin led the parish to confront the changing demographics of the neighborhood head-on. With the church coffers drying up and attendance waning, Father Begin not only tried to recruit new members from the African American community but also confronted the racism he saw among whites in his community and in his own congregation. “Fr. Begin made controversial statements and delivered provocative sermons,” according to the article in Cleveland Historical. “In one sermon he stated that ‘Adam and Eve were black.’ On another occasion he was overheard commenting, ‘God must have given the Negro something extra in virtue because of the way we whites have treated them.’ He looked to the increasingly Black area between Carnegie and Central as “a vast potential missionary [field] which we have neglected.” Begin's “anti-bias” efforts worked, at least in part, because St. Agnes parish was somewhat integrated during the 1950s. In fact, Begin once told the St. Augustine Guild, the Catholic interracial group of the Cleveland Catholic Diocese, that the parish had been integrated since at least 1949. “You may not realize it, but I never mentioned the word ‘white’ or ‘colored’ since I have been here,” the PD reported him saying. “I’m mentioning this to show that people in this parish do not think in this manner. They are a living example of the true unity of the church. I am deeply and profoundly proud of them and all the people of this neighborhood.” Even as Begin was openly anti-racist, the Plain Dealer refused to discuss race or the injustices of racism, segregation and income inequality in the neighborhood, evincing common attitudes of the time, stating, “Shortly after the bishop became pastor, the parish became a changing neighborhood. Parishioners who had lived there many years moved to the suburbs, and newcomers, many non-Catholics, moved in.” It appears Bishop Begin had no illusions that his work would solve the massive problems that existed in Hough and Fairfax, where whites had been exploiting Blacks by renting out homes for exorbitant prices at least since the 1940s. The end of World War II led to overcrowding across Northeast Ohio, but especially in the city of Cleveland, where most people still lived. (The population of Cleveland peaked at 914,808 in 1950 and has been declining ever since.) With pressure for housing as soldiers returned from the war, the federal government built highways and guaranteed mortgages that gave middle-class whites incentives to move out of the city, even as it denied those mortgages to Blacks. Meanwhile, banks redlined majority Black areas like Fairfax, making it harder to get a loan there (redlining is the practice of denying services or providing inferior services because of the racial composition of an area). Landlords took advantage of the poor who remained in the neighborhoods. Whites, fearing the racial changes taking place in Fairfax and elsewhere, fled the neighborhood in droves, compounding the problem of segregation and leaving a disinvested community behind, but also vibrant Black businesses and a thriving middle-class Black neighborhood. In addition to redlining, Blacks faced poor housing conditions because racist policies kept them out of other areas. It wasn't until the 1950s and 1960s that suburbs like Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights became integrated. Begin felt a bigger effort was needed, one that would create new housing for the poor in the inner city using federal aid. “Our efforts helped, but the area was too far gone physically for much to be done without city and federal aid," he commented. "At first, city officials shied away from the suggestion of the council that we rebuild or conserve the area. They thought the job was too big. They gave us a bit of lip service - that was all.” Begin saw the proposed University-Euclid urban renewal project as one answer. Unfortunately, that project led to the demolition of the Black-owned businesses at E. 105th and Euclid, the area known as Doan’s Corners that was once home to theaters, an ice-skating rink, and jazz clubs galore. In an interview when Begin was called to be the first bishop of Oakland, he said, “Hough will always be my home,” recollecting that he grew up there in the 1900s when the streets were unpaved and there were chickens in people’s yards. The neighborhood was changing then, he said – Poles, Lithuanians, Italians, Slovenians, and other immigrants were coming from Europe. “The neighborhood became American in the sense that people accepted each other,” Begin commented. “Even the few Negroes who lived here were accepted.” After Begin left, the church was staffed by the Trinitarian Fathers, an order within the Catholic Church that provides support to inner-city churches. On Sept. 27, 1966, St. Agnes marked 50 years. “Worshippers at St. Agnes Church yesterday were turned backwards in their thoughts to the priest and people who built the soaring Romanesque church 50 years ago – and forward to the parish’s new tasks in the inner city,” the PD wrote. But the church didn't have the money to maintain its massive building. In an April 14, 1973 article, Mary Jayne Woge of the Plain Dealer reported, “St. Agnes Catholic Church at 8000 Euclid Avenue in Hough is on Diocesan charity. Its massive Romanesque sanctuary, posh rectory and other ornamented buildings are window dressing for an operation that is as poor as a church mouse. On Sundays, 150 persons – three-fourths of them black – attend mass in the echoing auditorium built with a Hollywood flourish to accommodate 1,500. After the riots in the mid 1960s, the church was orphaned by 2,000 of its members, and its income dropped dramatically.” (Note: today, many churches would be happy with an average Sunday attendance of 150 people, but of course this paled in comparison to St. Agnes' heyday, when there were five services and attendance probably numbered in the thousands.) The Rev. George Huber of Holy Trinity Fathers told the PD, “We rattle around in the building.” He also remarked on how the church’s fine finishes were a contradiction to the surrounding neighborhood. His rectory office was wood paneled, with leaded glass windows and green marble fireplace. “I feel guilty working in a place like this,” he said. “A guy who’s hitchhiking, needs some help and rings the doorbell thinks I’m a liar when I say I can’t do much for him.” By June 1973, the diocese, facing a cash crunch, abruptly announced it was closing St. Agnes School. Attendance had dropped by half and the diocese believed that Catholic schools in the city could only survive if there was a smaller number. They said nothing about the school, but many feared it was next. Parents organized a protest and 30 people gathered on the sidewalk outside the doors. The 231 students and their families who went there were only given one week’s notice before being transferred to nearby Catholic schools like St. Adelbert and St. Thomas Acquinas. According to a PD article, $100,000 of St. Agnes’ school budget was subsidized by the parish or the diocese because many parents were too poor to pay the full cost of the yearly tuition, which at the time was $270. Additionally, enrollment was down, and the church hadn’t been able to raise enough funds to subsidize the school and keep it affordable for families as they had in the past. In a June 16, 1973 article with the headline, “Catholics face worst fiscal dilemma,” Woge reported, “The high cost of administering the word of God through parochial education has embroiled the venerable, once prosperous Catholic Diocese of Cleveland in financial trouble,” calling it “probably the worst cash dilemma in the mostly glittering 135 year history of Roman Catholicism here.” According to diocesan officials, the diocese had overspent on its income and was using $500,000-700,000 more than anticipated that fiscal year. Moreover, its reserves were depleted and it had borrowed as much money as it could. The diocese’s plan was to balance its books by closing St. Agnes school, and it was hinted that the church would be next. “Churches of negligible spiritual service to the communities around them may be sold,” Woge wrote. “Insurance costs are higher for inner city churches and schools than those in the suburbs.” (Imagine tearing down a church that was lauded as an ecclesiastical work of art when it was first built because it cost too much to insure! Yet this was likely the reality in the 1970s, when arson and other types of vandalism were rampant in Cleveland. Ironically, insurance in the area was probably higher due to redlining practices by insurance companies, too.) St. Agnes school didn’t go down without a fight. The Black parents who protested said the diocese was disinvesting in the church as well as the community. “As one mother at the meeting said yesterday, ‘It’s still going to be on our backs,’” the PD reported. Another parent commented that they do not want their children transferred to other Catholic schools. “I do not want my children going to a school where they are not welcome,” they said. “The schools in my area are white and they are definitely not welcome." And in a June 19, 1973 article headlined “Churchmen score school fund cuts in black parishes,” Woge wrote that a group of inner city pastors, minister and lay people were protesting the cutbacks, decrying what they called “the growing self-centeredness on the part of the diocese with regard to the abandonment of its already slender commitment to the inner city.” The group called the cutbacks “a morally uninformed act of political expediency” and in a letter, said they were “appalled” and found it “difficult to comprehend why it is that – in times of financial crisis which demand substantial cutbacks in funding – those parishes and schools serving the black community are the ones required not only to justify their existence but also to feel the heaviest effects of said crisis.” The letter railed against the lack of notice or help given to parents and said that Catholic Charities is “geared predominantly towards white middle class needs and services.” Black leaders called for changes such as including educational centers in parishes where schools were closed, a black auxiliary bishop, a vicar to be appointed to serve the needs of minority groups, an office of black affairs at the diocesan level, and a special task force to investigate inequitable distribution of funds between the suburbs and the city. The diocese responded by stubbornly doubling down on their commitment to the suburbs, saying there were needs there, too. The most reverend William M. Cosgrove, auxiliary bishop, commented that he “understands the pain that must be theirs … I am also aware that although the needs among the poor are extreme, there are similar problems in meeting the needs of the near poor and even the middle class.” He said he’d “exhaust every effort” to maintain services to the inner-city parishes but that “he is painfully limited by the resources available to him to do so.” He also called for public funding of private Catholic schools, a dream that was realized a decade later in the 1980s when this was pushed through the Ohio Statehouse, and that ultimately kept a number of Catholic schools afloat. However, it was too late for St. Agnes, whose fate was already decided. The school was set on fire and burned down not long after it closed. After the fire on Nov. 25, 1973, the diocese tore it down. Soon afterwards, on March 2, 1974, the PD published an article about St. Agnes Church getting broken into and vandalized. During the 1970s, arson and vandalism of city properties was an epidemic, and it was hitting St. Agnes hard. Thieves stole a hanging altar lamp valued at $2,000 as well as 10 large ornate brass candlesticks, each of which was valued at $500. The thieves borrowed a 10 foot stepladder in the church to steal the objects. They stole the keys from the church before entering at night. They also left a pile of refuse on the ground, which they apparently intended to burn. The theft was part of a rash of such burglaries, the PD said. The article cited windows stolen from a church and a 60 year old ornate bronze cross studded with semi precious gems that was stolen from Trinity Episcopal Cathedral on Sept. 17, 1973. Two years later, on Oct. 20, 1975, the PD published an article with the headline, “Buildings go - People first, Catholic spokesman says.” The shortsighted argument htat Diocesan leaders made the was that by tearing down the building, they were saving money so they could help more people. “The diocese, which has about 90 churches in Cleveland, is getting rid of the old buildings to serve the needs of people better, they said,” the reporter wrote. The Rev. John L. Fiala, diocesan secretary for parish life and development and a close aide to Bishop James A. Hickey, said the church “was not in the business of restoration of old buildings, and exists to deal with the needs of people.” It was hard to see how the Catholic Diocese could serve the needs of people in the Fairfax neighborhood by tearing down a landmark church, but that was their logic, anyway. The move, especially the decision to sell items in the buildings at auction, stirred up controversy. In several articles in the PD, a reporter interviewed people who were buying church pews, religious artifacts and other items for their private residences. A restaurant owner in Little Italy also bought some items for his eatery. the church sold these ecclesiastical treasures for pennies on the dollar, so the sale was quite popular. Someone even tried to buy the altar, but a church spokesperson said it was one of the few items that wasn't for sale. “Some persons have charged the diocese with not showing proper respect for the past and for attempting to make a profit from the moves,” the PD wrote. “Others have said it appears the diocese is attempting to escape from the problems of Cleveland’s east side and ignore black neighborhoods.” The warning of Monsignor Gilbert from 1934 comes to mind: “Let Cleveland go up there with them,” he said of the white men leaving the city for the suburbs, arguing that those who had the resources to deal with Cleveland’s problems should step up and help deal with them and that by abandoning the city they were causing it harm. Fiala went on to complain about the high maintenance costs of St. Agnes, essentially arguing that it was cheaper to tear it down. Notably, in its reporting, The Plain Dealer consistently failed to challenge the diocese’s arguments that because the surrounding neighborhoods were predominantly Black, the church was no longer sustainable. “All four of the parishes (to be closed) are in former ethnic neighborhoods settled mostly by Irish, German or Italians who built churches soon after their arrival,” the article states. “The three doomed churches are attended mostly by black persons, and in each case fewer than 100 come to mass in the massive cathedral-like structures. Father Fiala said there are about 10,000 black Catholics in Cleveland, and he emphasized that the distribution of the buildings does not mean that the diocese is not concerned with ministering in the black neighborhoods.” How was the diocese going to serve Black neighborhoods by closing churches, one wonders? And if it had to be closed, why couldn’t St. Agnes be repurposed for another congregation or group of people? That question was never answered in the reporting I read. With the original parishioners mostly gone, the only answer given was tearing it down, perhaps not unlike a village being burned by its fleeing inhabitants. According to a PD article, Father Fiala said, “One black member of St. Agnes said to me when we were discussing tearing down the building, ‘This is not a black church, it is a European church.’” He said the woman said, ‘It’s beautiful but blacks would never feel at home here, and it would not meet the needs of the black neighborhood.” Yet this argument belies the fact that St. Agnes had attracted many Black parishioners during the previous decades. In the end, Fiala said much of the negative reaction to tearing down the buildings came from former parishioners who no longer went there anyway, ignoring the protests by Black leaders in Cleveland. “It’s a nostalgic reaction,” Fiala said. Nostalgic indeed. And with that, one of Cleveland’s great historic churches was summarily wiped off the map. After the church was torn down. worshippers gathered in the rectory before ultimately merging with Our Lady of Fatima in Hough. The rectory stood for a long time but was finally torn down in 2009 to make way for a CVS Pharmacy. Nothing remains of the original St. Agnes today, save the bell tower and the stories that are carried in the hearts and memories of people who went there. “Let Cleveland go up there with them”: St. Agnes founder criticizes white flight to suburbs3/31/2024 A small classified advertisement in the June 5, 1922 issue of the Cleveland Plain Dealer read: “ST. AGNES PARISH. $8,800. Owner leaving city, will sacrifice this beautiful home, 8 rooms, and finished wood floor, oak doors and finish; in finest condition throughout; about $3,000 cash needed. For real values, see H and H Properties Company, corner of Hough and Crawford Road.”

This was the beginning of the outmigration my grandfather was part of when his family moved to Cleveland Heights in 1918. This “white flight” – mostly white, middle-class families fleeing an increasingly diverse neighborhood – would only accelerate in the coming years. Black families began moving into Fairfax during the 1920s and 1930s, as more and more African-American families came north during the Great Migration looking for work and a better life. Initially, because whites with racist beliefs would not rent or sell to them in other areas, Blacks in Cleveland were largely restricted to the Cedar-Central area. That began to change in Fairfax as whites moved out of the neighborhood in the 1910s and 1920s, and Blacks moved in. Father Gilbert Jennings of St. Agnes Parish talked about his legacy as church founder in a May 30, 1934 interview in the Plain Dealer. Saying he’s lived a full life and would be a priest again if given the choice, Jennings reflects on his legacy on the 50th anniversary of the parish. One of his accomplishments was doing away with “compulsory giving,” he says: “The priests used to go around with pads and pencils. But I disliked it. I told them, they have recording angels in heaven, and that’s their business. We might not know all the circumstances of any given case. We might not be able to tell whether a man was being decent. But they know up there. And it worked.” As I learned more about Father Jennings, I began to appreciate him more. My grandfather remembered the important role he played in the neighborhood. As the founding priest of St. Agnes, he built up the church from a small group of families to thousands of members, and with it, the neighborhood flourished around it, as well. Still, Jennings tells the reporter that his greatest regret is that his parishioners are moving out of the neighborhood, comments that would prove eerily prescient since white flight would ultimately lead to the church’s unraveling. “This was the bon ton residence section when I came out here,” he tells the PD. “The suburbs were just beginning to be developed. We practically built the institution. We finished the new church eighteen years ago. Then an exodus started for the Heights. It used to wrench my heart to see my good people moving away – but now I’m used to it. It leaves a man kind of alone.” He doesn’t just stop there, either. Even as he touts the fact that the school has the largest enrollment in its history that year, Jennings takes direct aim at white men like my great-grandfather moving to the suburbs. “These are the men who have made Cleveland and who ought to be more interested in the city than anyone else,” he tells the PD rather pointedly. “They’ve gone into the Heights, into Lakewood, into other suburbs. I wouldn’t mind that so much if they’d let Cleveland go up there with them. But they won’t. Then they complain about the sort of government Cleveland gets. It’s their own fault. With no vision or foresight they always have voted themselves out. I can’t understand their view.” “To me it’s one of the most politically regrettable things in Cleveland,” he adds. “We’re here at the mercy of things as we know they are.” This is 1934, but somehow Jennings is making an argument not only against suburban white flight but also for regional government, an idea that was ahead of his time. He goes on to say that he favors a unified county government instead of individual suburbs each with their own separate systems of government. Seeing the writing on the wall, he recognizes that once his parishioners move to the suburbs, not only will St. Agnes have fewer neighborhood parishioners, but the city itself will have fewer middle-class residents. They won’t have the ability to vote or shape what happens in the city, but only to complain about it from their houses atop the hill. Again, these comments are eerily prescient, as the city-suburb divide would plague Cleveland, and just about every other city across the U.S., for the next century, and it remains a stubborn problem today. In his candid interview with the PD, Jennings bemoans the changes to the neighborhood. As the area was developed, the original houses on Euclid Avenue were torn down for larger, commercial buildings – banks, theaters, music halls, or department stores. “They can’t say that I moved, but they moved my parish,” he says. “Of the original 80 or 100 structures when we started, I don’t think there is one left. The entire character of my parish has changed along with the change in the community. Most of our people moved up to the Heights when that development was begun.” Yet he holds fast to the idea that the St. Agnes building will stand for many more years. “It was built to last for centuries,” he tells the PD. “It will be here long after I am gone and forgotten.” In a followup story on June 5, 1934, Jennings says the parish’s true legacy is its community, not the building itself, as glorious as it once was. “If I weren’t balanced by a lot of common sense I might be carried away with the idea that I amounted to something,” Jennings says. “Much has been said of these buildings. But if I should go out of this world thinking that I had just put up some buildings at Euclid Avenue and East 79th Street, if I had to tell my God that I’d done nothing but a building job, I’d think my life had been a failure. My real purpose was to build up the Christian faith, the spiritual St. Agnes. If I haven’t got that accomplishment to take with me, I’ll have nothing. And if I have that I’ll have everything.” It’s clear from the legacy of the church, and how many people it influenced, that indeed that legacy is quite secure. On Jennings’ 80th birthday in 1936, the PD relates the history of St. Agnes, which it says “he founded before the end of the century, when Euclid Avenue was the fashionable residences street of Cleveland.” In the story, the priest repeats his complaint about people moving to the suburbs. As the PD tells the story, “Msgr. Jennings walked to a window of his office in St Agnes church rectory. He stood looking out on Euclid Avenue. Blocks of store buildings stand where there only were residences when he founded St. Agnes.” Decrying the middle-class white community that was moving out and leaving the poor behind, Jennings toes right up to the line of talking about racism in the city. “Cleveland Heights didn’t exist then,” the priest says. “Nor did many other suburban cities which attract so many desirable citizens. They have their business offices in the city. They say they cannot live here because city taxes are high. But they are better able to pay than many who live in Cleveland.” The “many who live in Cleveland” were almost certainly lower-income white and Black families. Jennings goes on to decry the lack of religion in people’s lives, and the fact that people do not feel duty-bound to go to church, a grievance that he’d surely feel more acutely today in that trust in Christianity and church attendance are down. However, in my opinion, Jennings’ statement about taxes is perhaps the most prescient of anything he says in this series of interviews. Although he never mentions race and racism (and nor, by the way, do the mainstream papers), he recognizes that there is a social justice and equity issue at stake here. White flight and outmigration are leaving low-income residents stranded in an increasingly poor city. Indeed, as many have pointed out, this problem of the so-called inner city or the “donut hole” of poverty would become the central problem faced by Cleveland in the next century, and it remains so today. Outmigration only increased post World War II and in the latter half of the 20th century, to the point where the city lost nearly two-thirds of its population, going from a peak of 914,808 in 1950 to 372,624 in 2020, according to the US Census. On April 17, 1941, the Plain Dealer included an announcement of Jennings’ death at age 84, paying tribute to the man who had not only built a glorious edifice in St. Agnes parish, but had also shaped the lives of tens of thousands of Clevelanders. To my great-grandfather and my grandfather, he was a civic and spiritual leader, and it’s easy to see from his remarks how much he got what was happening in the city at the time. Postscript: On July 31, 1949, the PD published a charming, romantic story about parishioners saving the bell at St. Agnes, a story that seems ironic now given the fate of the church 30 years later. The article, headlined “Save St. Agnes Chime with 4 Bolts in Time,” relates how the bell, which had been blessed and anointed with oil when it was installed seven years earlier, was saved from destruction. “The bell at St. Agnes Catholic Church, 8000 Euclid Ave., will ring as usual this morning,” the Press article relates. “But behind its chime, as a sort of counterpoint to its melodious signal to mass, will be a tale of four bolts … The overture to the dilemma began Thursday when a clanking sound was heard between the bongs of the four-ton bell. Yesterday, when an attendance investigated after the bell could not be rung, three of the four bolts holding the bell were found to be broken.” With the bell in danger of crashing more than one hundred feet in the bell tower, church leaders sprang into action. The parish nun telephoned T. Pierre Champion, president of the Champion Rivet company and a former St. Agnes student, and told him they needed the bell repaired or it wouldn’t ring the next day. Champion called George S. Case, board president of Lamson and Sessions Company, and according to the article, “Case recognized the size of the bolt, 1 ¼ by 12 inches as uncommon, but thought that some place in the plant at 1971 W. 85 Street they could be found. He left his home at 17414 South Woodland Road, Shaker Heights, went to the plant and, after searching through several bins, came up with precious sizes. The search was made unaided, since the plant was closed for the day. He picked up six of the bolts weighing approximately five pounds each, and hurried across town to the church.” Once there, he found Charles Moore, who worked for the Cincinnati company that repaired and serviced the bells, waiting to help him. “Hoping that the one remaining bolt holding the bell to its yoke would not suddenly break, Moore edged close and replaced the three broken bolts with the new ones,” the article says. “For added safety, he replaced the fourth bolt also.” The story also attests to the strong connections St. Agnes parishioners and school graduates had to each other. “Champion, at his home at 2489 Coventry Rd., Cleveland Heights, was amazed that he should be remembered by someone at the church from his former schooldays,” the Press story relates. “Case, a member of Fairmount Presbyterian Church in Cleveland Heights, said the mission was ‘fun’ - pleasant proof that one aloof from a plant’s equipment could still do the job.” Presumably, these white men who swooped in like white knights to protect the parish were long gone by the time the church was torn down 30 years later (although the belltower was saved and remains standing today, though without the 5,000 pound bell). St. Agnes Catholic Parish, a monolithic marble and stone church built in 1916 on Cleveland’s Millionaire’s Row, went from a packed parish with thousands of congregants and five masses each Sunday to a pile of rubble left for dead in a mere 60 years. As I wrote in my last post, all that's left now is a lone, crumbling church tower, which no one seems to care for, next to a vacant lot. Where the rectory and church stood is now a CVS with a drive through.

How did this happen? How did Cleveland lose the first Catholic church to be built on Euclid Avenue, a monument for the ages, one that was lauded as art when it was built? That's what I'll be exploring in this series of blog posts as part of the Fairfax Neighborhood History Project. (I hope to develop a separate website soon, but in the meantime Cleveland Historical and the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History have good entries.) I first became interested in St. Agnes because my grandfather grew up on E. 80th St. off of Cedar Ave. in Fairfax, and he was proudly baptized and confirmed at St. Agnes. He was also an altar boy there. His family left in 1918 as part of the white flight out of the neighborhood, a trend that accelerated as Black residents moved in during the Great Migration seeking better neighborhoods, schools, and living conditions. As I began digging into the history of St. Agnes -- I visited the site and posted pictures and some of my grandfather's memories of going there as a kid in my first post -- I realized there was more to the story. Historians blame the Hough Riots, when a white bar owner in Hough refused to give a Black man a glass of water, leading to protests and violence, for Saint Agnes' demise. They also cite a lack of money for upkeep and the fact that parishioners had moved out to the suburbs and surrounding neighborhoods were no longer Catholic. It’s a familiar story in cities across the U.S.: As Catholics decamped from the city and “non-Catholics” moved in (read: Black Protestants) attendance and support dwindled. With repairs needed, not enough money, and thieves looting the church -- after looters stole the copper drainpipes in the 70s, the priest complained, "we may wake up one day and find the whole church is gone" -- the diocese tore it down. Yet less magnificent buildings in Cleveland have been saved (many of them on the whiter, wealthier west side). St. Agnes could have been given new life, like so many Protestant churches in the neighborhood. Instead, it was torn down, ignoring community protests and outcries, including Black leaders who said the Catholic Church was turning its back on the inner city. Its downfall was decades in the making, but in a period of just a few years in the mid 70s, the school was set on fire, the church was looted, and finally it was sold off piece by piece before the diocese knocked down its Bedford stone blocks with a wrecking ball. It was a moment of communal blindness, a sudden act of violence that left a hole in the ground. In this post I'll explore the early history of St. Agnes, from 1893 when it was founded up through 1916 when the "new" church was built. I’ll use the Plain Dealer and Cleveland Press archives and other sources to tell the story of how St. Agnes came to be, its significance and growth. My hypothesis is that while St. Agnes was built to serve a growing white Catholic community, as they fled the area in the decades after Blacks moved in, the church wasn't prepared to grapple with the area's poverty and discrimination. In the 50s and 60s, a pioneering pastor moved in who tried to serve the surrounding community. Yet because the diocese did not see itself serving the Black community, most of whom were not Catholic, they ultimately neglected the church, couldn't find the vision or money to fix it, and then tore it down in a desperate bid to rid themselves of a problem they’d helped create. The original St. Agnes was a modest wood structure built in 1893 at the corner of Euclid Ave. and Hilburn Ave. (now E. 81st St.). In my last post, I wrote about how a group of Catholic women in Hough had petitioned Bishop Richard Gilmour to establish an English-speaking Catholic church on Euclid Ave. It was aimed at serving the growing number of middle-class and upper-middle-class German and Irish families living in the area who were Catholic. There were many Protestant churches on Euclid, but there were no Catholic ones at the time, so the building of St. Agnes meant Catholics, who a generation or two before had faced prejudice from native Americans who saw them as bringing un-American ideas from Europe, including socialism, to the U.S., had arrived. Euclid Ave. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was home to the mansions of wealthy Clevelanders like John D. Rockefeller, Marcus Hanna, Jeptha Wade and others, so it meant they'd made it, in a sense. St. Agnes was part of the outward migration of wealth along Euclid Ave. to what was then called the "east end," an undeveloped part of the city rapidly filling up with new development. When the church was dedicated on September 24, 1893, it was envisioned that it would soon be replaced by a much larger structure to serve the growing congregation. That ended up taking more than 20 years, yet Father Gilbert P. Jennings, the founding pastor, shepherded that vision to reality and went on to serve the church until he died in 1941. When The Plain Dealer covered the dedication of the new building by the Rt. Rev. Ignatius F. Horstman, bishop of the Catholic Diocese, it wrote, “St. Agnes Church is not an imposing structure. The present structure, however, is but a temporary one and within a few years it is predicted that the Episcopal residence and the central parish will be located on the present site of St. Agnes church.” The vision was grand – St. Agnes would tend to the spiritual needs of this growing area, spread Catholicism, and foster other churches. Addressing the congregation, the bishop "alluded to the fact that the planting of St. Agnes church was a pioneer work and like so many labors of the world the work is done by one generation and the fruits of its toil are enjoyed by the next," the PD wrote. Horstman went on to laud the growth of the Catholic Diocese, which had grown from Our Lady of the Lake, a wood frame church in the Flats which had served German and Irish immigrants in the 1800s until it was torn down, to monuments spreading throughout the east and west sides of the city. "Each new church of today would become the mother of other churches," he said. In June 1894, a festival was held on the empty lot next to the church, drawing over 1,000 people and raising money for the parish. Six months later, Bishop Horstmann preached to a packed house about the life of St. Agnes, the martyred saint that gave the church its name. (Catholics believe saints can be prayed to for help, unlike Protestants who believe people should pray directly to God. I was raised Protestant, and my grandfather, who grew up Catholic, later attended the same Presbyterian church I grew up in.) Catholic history holds that St. Agnes was born of noble parents in 291 and at 13 years old was arranged to be married. She had “numerous suitors,” but had already promised her life to God. “When sought in marriage she gave the answer, ‘I belong to the one who is not of this earth; Jesus Christ,’” Horstman told the rapt audience. Her parents and others, angry at the young teenager's rebellion, threatened her with “fire, the rack and torture of every kind,” and even “accused her of being a Christian," which was seen as a transgression against the Roman empire. Her punishment was exposure in a public brothel and being offered up for sexual conquest. “If you are vowed to a heavenly spouse, I will see that you do not go to him chaste," the praetor, a type of Roman magistrate, pronounced. However, Horstman related, “no one dared approach her, except one, and as he came near her he was struck blind.” When the praetor learned of this, he ordered that she should be beheaded in a public execution. There's no telling what this story meant to the congregation, but perhaps they took meaning from St. Agnes' brave defiance of her parents' cruel dictum and her faith in God even in the face of death. In Latin, Agnes means “lamb” and in Greek it means “chaste and pure.” Horstman told the church she was the “patroness of this parish” and a special protector of those who worshiped there. In 1903, St. Agnes school was built. Father Jennings preached the importance of parochial schools; they were there to “train the heart and mind” and help raise good Catholics. In an August 31, 1903 article in the Plain Dealer, he warned his parishioners against sending their children to public schools, arguing they were "vitally and fundamentally wrong" because they don't "train man's heart towards God." Any parishioner who sent their kids to public school was doing so against the “earnest protest” of their pastor and the bishop, he said. When the school opened in September 1903, the Plain Dealer called it “probably the finest parochial school building in the Diocese of Cleveland," praising its large rooms, lighting, ventilation, and modern construction. St. Agnes School had a large assembly room on the third floor that could fit more than 800 people. To accommodate students, two more nuns from the Sisters of St. Joseph were added, making eight total. (I'm scratching my head thinking of eight nuns ruling over 350 schoolkids -- no wonder they used rulers to rap their knuckles, there was likely no other way to maintain order.) A January 10, 1904 article after the dedication said that the new school was “one of the handsomest and most substantial buildings in the city and is considered a model of parochial schools for the Cleveland diocese” and that the three-story building was “imposing in appearance. It is built of buff Amherst stone and is Romanesque in style.” In both articles, the PD praised the stone building as “practically fireproof," as fire was a major threat to wood buildings at the time. The paper lauded its five large modern school rooms, each 28 by 32 feet, on the first and second floors, as well as four smaller recitation rooms where students were taught special subjects and recited their lessons. The auditorium had an inclined floor, vaulted ceilings, a gallery, and “the lighting is of handsome electric fittings” (gaslights were common in the 1800s and lasted until the early 1900s, when they were replaced by electric lights). “The acoustic properties are said to be perfect," the article said. "The stage is roomy, with dressing rooms on either side. The auditorium will be a splendid place for school and parish entertainments.” Church leaders were practically bursting with pride when the school opened that school year: “Father Jennings said that creditable as has been the work of the past, the future, he hoped, would excel it,” the Plain Dealer wrote. When it was dedicated, the Rt. Rev. John Lancaster Spalding, bishop of Peoria, Illinois, said the school was a centerpiece of the parish and if congregants educated their children there, they’d grow up to be good Catholics. “Nothing that can ever be done in this parish will equal in importance the dedication of this school," he boasted. The school was completely free for parishioners, a sign of the church’s wealth and evidence of its formula of investing in Catholic education to spawn adults who would go to mass each Sunday, just as their parents had. By 1905, the fast-growing St. Agnes added a fifth service to accommodate the growing number of parishioners worshiping there. There were English masses for adults at 6, 7:30, 8:45, and 10 o’clock on Sunday mornings, The PD noted. A fifth mass at 11:45 was added for children, which was considered innovative at the time, “it being the latest hour at which a service is begun before noon at any of the city churches of that denomination.” A third priest was hired to help with masses, something that was notable since only the city's largest churches boasted three priests. Father Jennings was not only the spiritual leader of St. Agnes, but also a leader within the wider community. “A pioneer in the east end, he builds one of the city’s biggest churches,” a 1909 PD profile of Jennings crowed, going on to say, “As the founder of St. Agnes parish, the first to build a church on Euclid Avenue, Rev. Mr. Jennings is the recognized leader of Catholicism on the east end.” “Twenty years ago, the idea of establishing a Catholic church on Euclid Ave. was dismissed as visionary, said Father Jennings yesterday,” the PD wrote. “Now Euclid Avenue is the center of St. Agnes parish, one of the largest parishes in the city. Moreover, St. Agnes church has today three other parishes in the east end as its offspring.” On his 25th anniversary of being a priest, the diocese threw Jennings a large banquet where he was presented with a purse of gold and a picture of the Madonna. That evening, a “jubilee allegory” specially written by the Sisters of St. Joseph was performed by 130 schoolchildren. The very presence of St. Agnes was seen as a triumph over adversity, a realization of the vision church leaders had for a growing, thriving parish community. The PD wrote, "In the sixteen years of the pastorate, Father Jennings’ most serious problem has been not how to get members but how to take care of the ever increasing numbers that come to St. Agnes.” By 2012, St. Agnes had paid off their debt of $16,600 on the old building, and they had a $6,000 down payment to build the new church. Two years later, on July 6, 1914, church leaders laid the cornerstone for the new St. Agnes parish, which cost $160,000 to build (about $5 million today). Before arriving in his automobile for the ceremony the Rt. Rev. John Farrelly, bishop of the diocese, was “met at Euclid Ave. and E. 85th St. by 300 men of the church. They formed an escort for him from that point to the parish residence.” He blessed the building, using a trowel to scratch a score of crosses on the stone block on the eastern side of the sanctuary. Farrelly then walked around the building sprinkling it with holy water before giving his sermon. The new St. Agnes married art and religion to create a new spiritual monument on Cleveland’s east side. “The new church edifice has been the object of a great deal of interest among art lovers and hundreds have visited it since it has been possible to admit other than workingmen to the interior,” the PD wrote of the church’s opening in 1916. “The new St. Agnes Church represents a noteworthy example of the unity of religion and art. Rev. Father Jennings determined at the beginning of his plans for the new edifice to erect a church building that was to be worthy of its high destiny as a place of Catholic worship and a civic monument.” the architect was John Comes, an ecclesiastical architect out of Pittsburgh, and Jennings was highly involved. The design was French Romanesque because it was considered adaptable and cost effective, “expressing the ancient and modern continuity of the church, and also the power of her adaptability to the language of the day." In addition to the beautiful stone and marble design, the interior had a “large auditorium-like nave containing nearly all the pews between the columns. By this arrangement those in the church will be able to see the priest, whether he be at the altar or the pulpit.” The nave was 40 feet wide by 65 feet high by 175 feet long. The sanctuary could hold 1,100 people, so on a Sunday with five masses, as many as 5,000 worshippers crowded into the space, filling St. Agnes with their sounds of their voices raised in song and praise for God. The interior of the church was painted by artist Felix Lieftrichter and contained a “feeling of solemnity and grandeur,” The Plain Dealer wrote. “The monumental figure of Christ in majesty seated on the throne, ancient symbol of power, surrounded by a cluster of cherubim holding the seven lights of the apocalypse, forms the central and dominating feature of the composition,” while the 12 apostles below represented mankind. The “Eternal Father” was painted on the vault of the apse, “symbolizing the redemption of mankind through the son of God.” There was more: “Between the figures of God the Father and God the Son is the dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit surrounded by seven golden flames, symbolic of the seven gifts of the holy ghost, forming together the traditional representation of the Holy Trinity. The figure of the eternal father is represented with arms outstretched in a bestowing attitude as father of the universe, and surrounded by a large circle symbolic of eternity, which is formed by the signs of the zodiac on a background of deep blue studded with stars and planets. “Kneeling on the base of the throne at the feet of our Lord are the figures of the Virgin Mary and St. Agnes in attitude of supplication, representing the saints of the church as intercessors for mankind at the throne of God,” the PD wrote. “On either side of the central figure is a row of richly clad angels holding in outstretched arms, symbols of the 7 days of creation.” Overall, “the upward and outward movement of these figures” creates a “feeling of solemnity and grandeur.” The inscription on the altar reads, “Behold the lamb of God who taketh away the sins of the world.” The theme of the art is the redemption of mankind through Christ, the PD said. In June 1916, the church was dedicated. The PD headline crowed, “Thousands throng Euclid Avenue and many jam into the nave of the new edifice.” Crowds began to form at 9:30 am for the 11 am service, and police handled the traffic. Hundreds processed from the parish house to the new church at 10:50 am, headed by a cross bearer. The visiting bishops wore “purple cassocks and birettas. Bishop Farrelly wore a gold cope and mitre. His left hand carried the crozier, the pastoral staff of office, and with his right hand he blessed the people as he passed,” according to the Plain Dealer. Once the service began, the Rt. Rev. James Hartley, bishop of the Diocese of Columbus, recited the words of Matthew to the crowd, “And I say unto these, that thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” The PD wrote, “To the worshippers and their pastor, the words of Bishop Hartley came with a new meaning. The church that for years had been their dream was at last a reality.” In 1920, a book was published, "St. Agnes Church, Cleveland, Ohio: An Interpretation," that discussed the artistic and religious significance of the church as ecclesiastical art and architecture. Author Anne O'Hare McCormick opines that St. Agnes was "conceived in faith and built in love" and that "the soul of the builders speaks from its walls ... it is clear and simple, like the faith of the earlier age that inspires it." She goes on to talk about how St. Agnes was significant not only in Cleveland but also nationally as a distinguished work of art, and it was frequently used as a model in lectures at the Cleveland School of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art. St. Agnes' Romanesque style of design was seen by McCormick as "a distillation of the art and aspiration of the most Catholic age in the history of the world ... St. Agnes embodies the authentic spirity of the heyday of art and of faith..." The opening sentence gives you a sense of why this church was so beloved and admired, as McCormick describes it in gracious, detailed prose: "As you look at the Church of Saint Agnes from the other side of Euclid Avenue -- unfortunately there is no stone-paved French place or gross-growth Italian piazza to give you better perspective -- your first impulse is to look again. A church so different from any church in Cleveland cannot be passed with a casual glance. Your next is to wonder a little at the effect of what you see. Walls of smooth gray Bedford stone rise out of a broad sweep of steps, three deeply recessed doors open under round arches, a pillared arcade runs beneath a great rose window, a carven crucifix tops a turreted gable, and back of all, overshadowing gray walls and red-tiled roofs, a tall tower, strong and steadfast, stands like a sentinel." When St. Agnes celebrated its dedication in 1916, A block away stood the old wooden church, soon to be demolished. “Perhaps the conflicting emotions of a family leaving a home it has long outgrown, but which is dear, nevertheless, for one that embodies the dreams of years, were responsible for the impressive touch that concluded the ceremony … that final scene will live long in the memory of all who witnessed it,” the PD wrote. “As the notes of the last gospel died away, that great congregation stood. The notes of the organ rolled across the church, and the worshippers, as one person, gave utterance to their feelings of Thanksgiving in the hymn, ‘Holy God, we praise thy name.’ A few moments later, the parishioners followed the procession of clergy to the street and the dedication was a matter of diocesan history.” The bishop urged the parishioners to be leaders in their community, and to use the church to light the way for the city. “You have a magnificent new church, but remember there are no parish aristocrats,” he said. “The Catholic church has always been strongest in its democracy. Your church edifice is an example to be followed by Cleveland. Let your lives be examples to be followed, also.” Sixty years later, the church had effectively been abandoned by its congregation, which had moved out of the neighborhood, and St. Agnes was history. Today, a stately bell tower is all that's left of St. Agnes Parish, a Romanesque stone church that stood on Euclid Ave. between E. 79th and E. 81st Streets in Cleveland from 1914-1975. When it was built, it served the growing number of middle-class and upper-middle-class Catholics in the Fairfax and Hough neighborhoods, including Irish and German immigrant families like my grandfather's. As whites fled and Black families filled up the neighborhood, St. Agnes served the growing Black community, until finally it succumbed to decay and neglect.

In the late 19th century, a group of Catholic women in Hough petitioned the bishop to establish a parish at this location to serve the growing number of German and Irish families. The church was started in 1893 and the school and original church building opened in 1894. Church leaders broke ground for the stone church building in 1914. Its stature shows the wealth and size of Cleveland at the time. St. Agnes was built of heavy Bedford stone and had three imposing recessed doorways on the facade. Photos show tall, heavy, ornate metal entry doors. There's a huge circular rose window above the doorway, a clay tile roof, and impressive stonework including a cross high atop the building. The bell tower is next to the church. Based on the photo above, there's a large home to the west, and what looks to be an even larger building behind that. My grandfather, Lee Alfred Chilcote, who I'm named after, walked to school at St. Agnes every day when he was growing up. He was born in 1907 and his family lived on E. 80th St. south of Cedar until 1918 when they moved to Cleveland Heights. He writes about St. Agnes, where he was confirmed and where he was also an altar boy, “I was a Catholic until I was 11 years old, and I went to St. Agnes Church and had my first Communion and Confirmation there. At that time, Father Jennings was the Pastor. He was quite a man. St. Agnes was located at 79th and Euclid Avenue. I can still see it, it was made of a somber-looking Ohio stone, big blocks, built like a fort. It is torn down now. Those nuns were very, very strict and they used to carry big straps on their belts at the time, and if you didn’t behave you got a big whack. There was no question about disciplining children in those days.” In the photo above, taken in the 1910s or 1920s around the time my grandfather went there, I'm struck by how young the tree is, the brick street with streetcar tracks on Euclid Ave., and what looks to be a welcoming plaza in front of the church. Based on photos which I found with the help of folks at Cleveland Public Library, upper Euclid Ave. changed dramatically from 1900 to 1920, from a quiet, sleepy street that horse-drawn carriages clopped down to a bustling thoroughfare filled with streetcars and, beginning in the 1910s, motorcars. Euclid Ave. in Fairfax currently lacks any sense of place, because it's so chopped up by different uses, with the few remaining older buildings set close to the street and others, like the CVS, out of context. I'm also struck by the imposing brick house to the west of the church, which is probably only 10 feet away from St. Agnes in a density typical of the time, and I wonder if it wasn't the home of the St. Agnes priest. St. Agnes originally represented the growing strength and influence of Catholics in Cleveland, but it adapted to the changing neighborhood and served Black families who moved into the neighborhood after the Depression and World War II, according to Cleveland Historical. However, the school closed in 1970 and the parish struggled. One of the reasons for the closure, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, was the decline of the neighborhood overall following the Hough Riots of 1966 (also called the Hough Uprising), when a Black man was refused a glass of water by a white bar owner, leading to dayslong riots. In the ensuing protests, four Black people were killed, 50 were injured, and the National Guard was eventually called in to quell the violence. St. Agnes later merged with Our Lady of Fatima in Hough, and the church was torn down in 1975 (check out this piece by Tom Matowitz about its demise). As for me, I doubt the Hough Riots directly led to the closing of St. Agnes, which could be seen as akin to blaming the neighborhood for the church's shuttering, instead of the Catholic diocese that decided to close it. I'm going to try to dig into this in my research. This week, I visited the church site and walked around a very depressing, forlorn patch of land at E. 81st St. and Euclid Ave. in Fairfax. On the corner where the church once stood, there's a CVS with a parking lot facing Euclid Ave. The church tower to the east, which looks to be about five stories tall, is still standing, but it's slipping into decay with holes around the foundation and vines creeping up the stone. The empty lot around it is fenced off with orange construction fencing, and the property is for sale with a big sign out front. There's a cell tower in the rear of the property (it's not the same as the bell tower, although that would be neat). According to property records, the church site was owned by the diocese until 1982, when it was transferred into private hands. The CVS was developed around 2007, but the bell tower site is owned by Good Karma Broadcasting and its only use appears to be the cell tower. I'll post more here as I learn more in the coming months (if you have info or tips, you can reach me at [email protected]). She's a beauty, even on a gray winter day! Thanks to Detroit Shoreway based painter Felix Rentas and his crew, the painting was finished on 7216 W. Clinton Ave. during a few warm days in January before the winter storm hit. There was a lot of prep work, of course, including removal of hundreds of nails, filling nail holes, and smoothing imperfections. But after the concrete siding was removed, overall, it turned out the original wood underneath was in remarkably good condition. The colors are all from the Sherwin Williams Victorian palette. There are five of them - the blue body color (Rookwood Blue Green), the terra cotta trim (Rookwood Terra Cotta), the salmon accent color (Renwick Rose Beige), the deep brown for the porch and cedar shingles (Rookwood Dark Brown), and white for the storm doors, ceilings and windows. The signature oval window that you see on the front of the house was refabricated by DW Ross, after it basically fell apart, completely rotted through, as soon as we removed it from the house. Rather than replacing all of the windows, which was the original plan but turned out to be well beyond my budget, we've been slowly replacing the glass inserts, about one-third of which had either broken panes or broken seals. The railings are obviously new and that's one of the items left to be painted. This house is available for rent on Airbnb here, and so far, it's getting bookings: https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/998349242597093217?check_in=2024-02-04&check_out=2024-02-09&guests=1&adults=1&s=67&unique_share_id=16d6af70-cf6b-4b13-a96f-44abf75ecad7

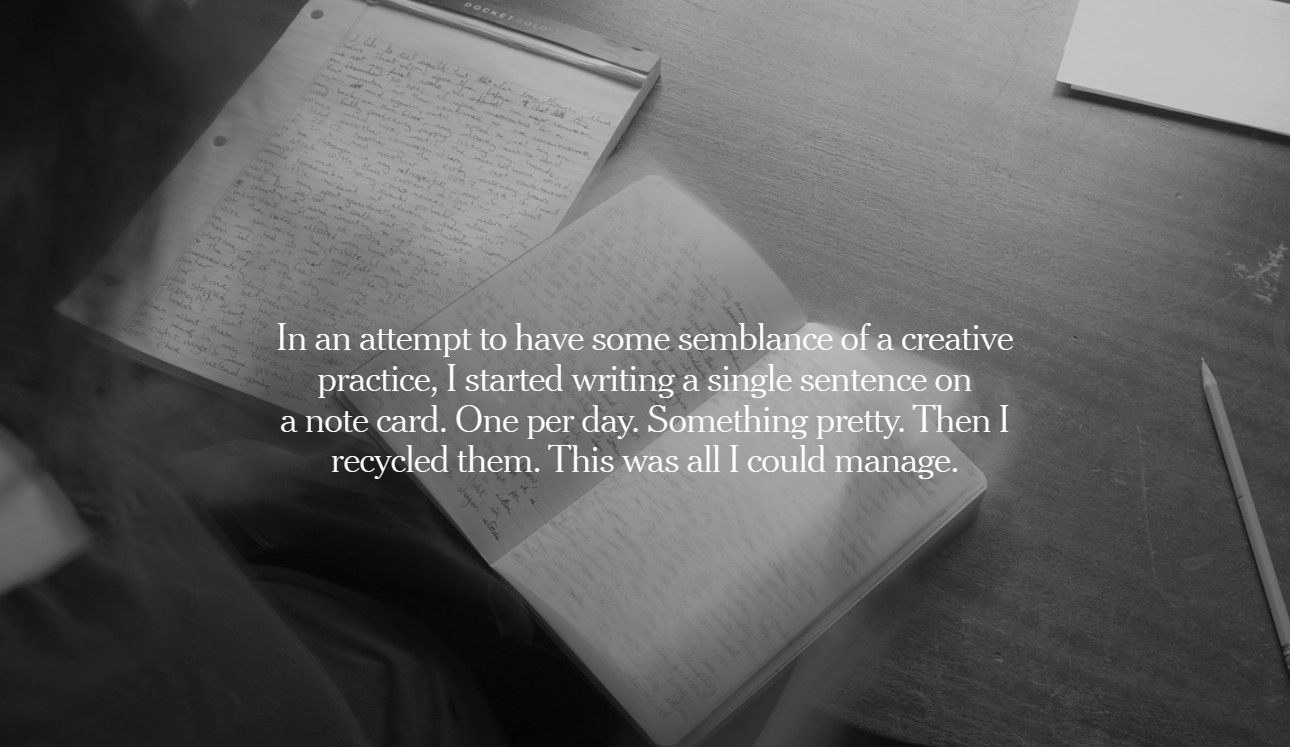

Building on my experience repairing and overseeing rehabilitation work on historic homes, I'm moving in the direction of establishing a real estate repair, contracting, and consulting business where I help homeowners, developers and others rehabilitate older homes and build new homes that add to Cleveland’s revitalization. Some of the services that I offer include house cleanouts, renovation coordination, design, prepping homes for sale, marketing, and, as a licensed realtor, selling homes and working with buyers to find a home that suits their needs. Contact me for details at [email protected].  The Other Black Girl This poppy-yet-literary novel by Zakiya Dalila Harris is a satire of diversity in the book publishing industry. Harris, who is the sister of Aiesha Harris, a reporter with National Public Radio, worked in book publishing for several years before taking time off to write the novel. It sold for over $1 million and is now a Hulu series (I haven’t watched it). Basically, Nella, the main character, is the only Black employee at the publisher where she works, until Hazel is hired. Hazel is everything Nella, who grew up in white suburban Connecticut, is not – she’s from Harlem, wears long flowing locks, and embraces her family’s activist heritage. Nella, who is quietly trying to push diversity in the workplace without losing her job, is at first excited that there’s another Black girl she can bond with. But something’s up with Hazel. I didn’t love everything about this novel, whose plot can get a little meandering at times, but the descriptions of white fragility and the moral dilemmas of speaking up in the workplace seemed pretty spot on. Listen to Zakiyah Harris on NPR’s It’s Been a Minute. Michael Stipe’s slow reinvention REM, one of the greatest bands of all time, disbanded in 2011. Since then, frontman and singer Michael Stipe has published books of photography, exhibited visual art, and performed at a few concerts and rallies. He hasn’t, however, as a recent article in the New York Times by Jon Mooallem points out, done the thing fans most want him to do – make music. That could change soon – or not. Stipe has been working on an album of solo material for nearly five years, but he hasn’t released anything yet beyond a single. It was supposed to be out in early 2023, but it’s been delayed multiple times. “I’m in no rush,” Stipe said, while at the same time remarking, “I’m at the age where I’m realizing, OK: All these ideas I want to focus on, I’m not going to have the life span to be able to complete all of them.” I liked this article for how much the author got in the subject’s head – from giving us anecdotes of Stipe’s childhood, to demonstrating how his uniquely creative brain pings from one thing to the next, to giving us a scene where he is in the same studio as Taylor Swift and runs into Jack Healy of the 1975, who cites REM as a big influence. Mooallem shows us what it’s like to be an aging rock star whose influence looms large but who is out of step with pop culture, where rock music is for old people. I think anyone who’s had to reinvent themselves will be able to relate. Read the article. Brandy Clark In 2020, the New Yorker published an article with the headline, “No one is writing better country songs than Brandy Clark is.” This month, David Remnick did an interview with Clark about her 2023 self-titled album. She wanted to call the album North West, after a song she wrote about growing up in that part of the country, but when she told people this, they immediately associated the words with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian’s child, so she changed it. Clark, a lesbian who has written songs for country artists, leans into Americana, which she calls “country music for Democrats,” amidst the culture wars that continue to rage in country music. Her simple songs exhibit many of the things I love about folk and country music – its lyric poetry, its storytelling, its emotional truths. Standouts are “Buried,” an achy love song, “Northwest,” about the pull of home when you’re away all the time, and “She Smoked in the House,” about her old-school grandmother (“lipstick-circled butts in the ashtray” is one of many good images). Allison Russell This is someone I just discovered this month after Terry Gross interviewed her on "Fresh Air." Allison Russell released an album of powerful, redemptive songs this year, “The Returner,” that grapples with freeing herself from sexual abuse by her racist father. These are powerful, redemptive songs. Check out the interview here. Dan Savage’s love and sex advice for the new year I first started reading Dan Savage when I was in my 20s, young and trying to figure out my own attitude towards sexuality and relationships. Savage, a gay man, is best known as a sex advice columnist, and he and his partner have been in a committed-yet-open relationship for more than 30 years. I’ve always found Savage’s words to be powerful and insightful and to offer something for all of us. And, frankly, these are perspectives about monogamy, commitment, sex, marriage, and relationship tradeoffs of relationships you don't often hear in the media. One of the fascinating statistics he cites is the growing number of people who identify as queer (20% of Generation Z, according to Savage, compared with 10% of Millenials and 2% of baby boomers – how typical, ha, that the statisticians have skipped over Generation X, my generation, as Katherine pointed out). This interview with Ezra Klein is long, but worth a listen.  A week and a half ago, The New York Times published an essay called "Rebuilding myself after brain injury, sentence by sentence" by writer Kelly Barnhill about her experiences with a traumatic brain injury. Barnhill, who writes children's literature, fantasy and science fiction, fell down the stairs and got a concussion that left her deprived of the ability to do her job writing fiction or even remember words and their meanings. "Healing a brain injury is the process of rebuilding not only tissues and cells and the connections between those cells, but also memory, thoughts, imagination, and the fundamentals of language and our very concept of ourselves," writes Barnhill, an author of children's literature, fantasy, and science fiction. "I am rebuilding myself, you see. Right now. Sentence by sentence." She goes on to cite the fact that "1.5 million Americans experience a traumatic brain injury each year," and that "many more suffer neurological symptoms from other issues, including long Covid, and experience the same kinds of cognitive unraveling that I have learned to live with over the past two years." It's a tough, moving piece, as she details with excruciating vulnerability all of the things she's lost in the wake of her brain injury and is trying to rebuild, such as remembering the word for "sock" and "stripes" and going to doctor after doctor seeking answers. The essay itself took her months to write, she says, and lately she's been jotting a few sentences at a time down on notecards in an effort to get her strength back, but that's about all she can manage. She goes on to ruminate on the relationship between memory, story and creativity, and to suggest that without these things, we're not fully ourselves. "Am I still me?" she asks. "Will I ever be me again?" I taught this essay in my Creative Nonfiction class at the Siegal Lifelong Learning center, because it's an example of a public essay that's also incredibly personal, and one that weaves the public and personal together quite effectively and powerfully. I think I related to this essay so strongly because of my own experiences with creative loss. I've never had a traumatic brain injury, but I've struggled with the inability to write in recent years and I've often wondered, just as Barnhill does, if I'll ever write again. But no matter what I go through or what happens to me, not only does my desire to write never go away, but my ability to write stays with me. Maybe this is because even when the brain endures trauma, it often has the ability to heal. "Cognition requires rest," a doctor tells Barnhill, when she asks when she's going to get better. "Some of us need more rest than others. But your brain is learning. It doesn't know how to stop learning. Give yourself a break and let your brain do its job." |

Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed